By applying force on the table and spindle and watching for movement I was able to determine that the bulk of the backlash is the result of slop in the bearing blocks. It seems as though the dials at the end of the lead-screws have worn into the mating part enough to allow the stepped down portion of the lead-screw to poke up enough to cause the slop. My remedy was to use a half-round needle file to chamfer the dial enough to allow the lead-screw to protrude further into dial. This reduced the backlash to .002 or thereabouts instead of the .015 I started with on the Z axis. I wasn't able to finish the Y axis but I hope to get to it tonight. I need to get the backlash down to .002 on all axiis so that I can convert the mill to CNC. I've got stepper motors on order so the conversion is not far away.

Friday, October 01, 2010

Still chasing backlash

By applying force on the table and spindle and watching for movement I was able to determine that the bulk of the backlash is the result of slop in the bearing blocks. It seems as though the dials at the end of the lead-screws have worn into the mating part enough to allow the stepped down portion of the lead-screw to poke up enough to cause the slop. My remedy was to use a half-round needle file to chamfer the dial enough to allow the lead-screw to protrude further into dial. This reduced the backlash to .002 or thereabouts instead of the .015 I started with on the Z axis. I wasn't able to finish the Y axis but I hope to get to it tonight. I need to get the backlash down to .002 on all axiis so that I can convert the mill to CNC. I've got stepper motors on order so the conversion is not far away.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Jury Rigged 230V for South Bend Lathe

Monday, March 29, 2010

Atlas Power Hacksaw

Friday, March 19, 2010

Bike Frame Building Course: Part 2

Day two of the bike frame course was a very exciting one. Not only was it my birthday, but I finally got to use a TIG welder, and a nice one at that. On the end of Day one I had mitered and prepped tubes to practice welding on. Toby set the amperage on the Miller Dynasty 200DX to 65 and turned on the argon. He then handed me a welding mask to protect my eyes from the bright arc and did a demo weld while describing the steps as he went. I'll do my best to describe the process, but I doubt that I can do it adequately.

First you put the tip of the tungsten up to the spot that you wish to start welding, with a gap between the tip roughly equal to the diameter of the tungsten. In this case the tungsten was 1/16". Next you press the foot pedal approximately 3/4 to full to initiate the weld. This particular TIG welder has a high frequency starting feature that makes it easier to initiate an arc. I've read that this is an important feature for welding CrMo steel because otherwise you have to do what is called a "scratch start" and run the risk of breaking off the tungsten tip into the weld area. This would leave a hard spot that would be prone to cracking.

Once the arc is started you must be sure to apply sufficient power to begin a weld pool. The weld pool is the molten puddle of steel formed when the electric arc heats the tubes being joined. It can be seen as a shiny spot that forms under the arc of the tungsten. The basic method used in TIG welding is to form the weld pool, insert the filler rod into the weld pool until the tip of the filler rod melts into the pool and makes it bigger, then move the pool toward the direction of the filler rod. This is repeated over and over along the length of the weld seem until it is complete. Before we do this though we first need to tack weld the tubes together so that they don't move much when heat is applied. This is done in the same way as described above, only you just get the weld pool started, add filler rod and then stop the weld instead of proceeding down the seam. Whenever you stop welding CrMo steel you should slowly let up on the foot pedal to allow the steel to cool slowly so that cracks don't form. Regardless of the material you should keep the torch in place after the weld until after the post-flow of argon gas shuts off. The post flow ensures that the metal is shielded from impurities in the air until the metal is fully cool. Okay, it's still frigging hot enough to burn the hell out of you, but it won't be hot enough to immediately oxidize.

The tubes used on high quality steel frame bicycles are wicked thin . This means that they are very easy to burn through. It also means that the weld pool is pretty small and can be difficult to see. The most difficult aspect to welding the frame that I found was seeing the weld pool well enough to tell when to add filler rod, when to move the arc forward, and when I burned through. I suppose it might be time to get glasses.

I made a few practice welds on the scrap tubing and I did pretty well. Certainly not as well as Toby did, but pretty darned well for my first time. You can see from my weld that it lacks the "stacked dimes" look that Toby's has. This is because I wasn't able to add the filler rod fast enough to create the ideal weld. Adding filler rod is quite difficult as it is done with the non-dominant hand, in my case the left hand. My left hand is usually used for such complex tasks as keeping papers from blowing away and filling the empty space in my left pant pocket. It should therefore be no surprise that it may take some time to get this action down to a science.

I made a few practice welds on the scrap tubing and I did pretty well. Certainly not as well as Toby did, but pretty darned well for my first time. You can see from my weld that it lacks the "stacked dimes" look that Toby's has. This is because I wasn't able to add the filler rod fast enough to create the ideal weld. Adding filler rod is quite difficult as it is done with the non-dominant hand, in my case the left hand. My left hand is usually used for such complex tasks as keeping papers from blowing away and filling the empty space in my left pant pocket. It should therefore be no surprise that it may take some time to get this action down to a science.Toby told me that he was surprised by how well I did considering my complete lack of welding experience. I've made some crappy MIG welds before, but these TIG welds came out so much nicer. It certainly helped that I had an instructor telling me what to do every step of the way. It was at this point that Toby said he thought that I was ready to start welding the main triangle of my bike frame together. That's right, it was judgment day.

As the main frame tubes were already

prepped for welding and placed in the jig, all we then had to do was to tack them together so that the frame could then be taken out of the jig and welded on the welding table. I tack welded each joint in about four places and Toby verified that the tacks were sufficient. We then removed the frame from the jig and placed it in a drill vise on top of the welding table so that we could orient it in a way that allowed easy access to the weld joints.

prepped for welding and placed in the jig, all we then had to do was to tack them together so that the frame could then be taken out of the jig and welded on the welding table. I tack welded each joint in about four places and Toby verified that the tacks were sufficient. We then removed the frame from the jig and placed it in a drill vise on top of the welding table so that we could orient it in a way that allowed easy access to the weld joints.The first joint that I welded was the top

tube to seat tube junction. I'm not totally sure why we started there. I assume that it was because these two tubes have the most similar thicknesses and were therefore the easiest to weld, thus making it a good place to get my feet wet. I then did the top tube to head tube junction, the head tube to down tube junction the down tube to bottom bracket shell junction and lastly, the bottom bracket shell to seat tube junction.

tube to seat tube junction. I'm not totally sure why we started there. I assume that it was because these two tubes have the most similar thicknesses and were therefore the easiest to weld, thus making it a good place to get my feet wet. I then did the top tube to head tube junction, the head tube to down tube junction the down tube to bottom bracket shell junction and lastly, the bottom bracket shell to seat tube junction. The Bottom bracket shell was pretty difficult to weld as it was much thicker that the down tube and seat tube, so it was a bit of a balancing act to apply enough heat to melt both tubes, without burning through the thinner ones. This was done partly by pointing the tip of the tungsten such that it was 2/3 on the bottom bracket shell and 1/3 on the thinner tube. This ensured that the bulk of the heat was being applied to the thicker area. There were a few instances where I did create some small holes and had to have Toby come over to fix my mistakes. This is where Toby really showed his skill and experience in filling holes I had just made in such a way as to make it barely noticeable. I was really in awe.

The Bottom bracket shell was pretty difficult to weld as it was much thicker that the down tube and seat tube, so it was a bit of a balancing act to apply enough heat to melt both tubes, without burning through the thinner ones. This was done partly by pointing the tip of the tungsten such that it was 2/3 on the bottom bracket shell and 1/3 on the thinner tube. This ensured that the bulk of the heat was being applied to the thicker area. There were a few instances where I did create some small holes and had to have Toby come over to fix my mistakes. This is where Toby really showed his skill and experience in filling holes I had just made in such a way as to make it barely noticeable. I was really in awe.Since it is presently more than a month since I took this frame building course the details are starting to get a bit fuzzy. As memory serves me, I was able to complete welding the entirety of the main triangle on day two. I do remember that I stayed pretty late, but it was likely because Toby and I got along really well and goofed off way more that we should have. Luckily for me I don't think that Toby had planned to leave early that week due to the fact that the North American Handmade Bike Show was coming up at the end of the week and while he wasn't going, he was letting a few of his friends use his shop to finish up some bikes for the show. Tony Maietta was finishing up a road bike with some S&S couplings that came out looking pretty sweet.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Bike Frame Building Course: Part 1

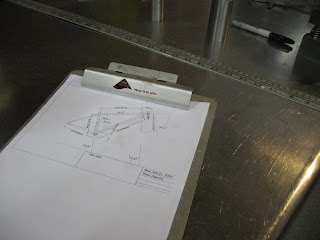

The whole experience was a good one. The shop that Toby has set up in Shirley, MA is quite impressive. It is located in a renovated mill that was once the home to a rope manufacturer. The brick walls, exposed beams, and large windows provide an atmosphere that really  makes going back to my cubicle in a windowless factory tomorrow even more difficult. The work are was well organized and clean. The only messes in the place were those made by me, or the two frame builders that Toby let borrow his space as they prepped frames for the North American Handmade Bicycle Show. On day one Toby and I sat down at the PC... er, iMac and designed my frame using a program called BikeCAD. The program is a user-friendly way to quickly input frame dimensions in order to spit out the necessary lengths and angles at which to cut tubes. The frame geometry that we decided to use was a cross between that used on the Ted Wojcik Monkeybutt and the Felt Nine that I demoed at Interbike East early this past fall. I decided to build it around a Fox F29 100mm fork, the dimensional specifications for which can be found on the Fox website if you really dig for them.

makes going back to my cubicle in a windowless factory tomorrow even more difficult. The work are was well organized and clean. The only messes in the place were those made by me, or the two frame builders that Toby let borrow his space as they prepped frames for the North American Handmade Bicycle Show. On day one Toby and I sat down at the PC... er, iMac and designed my frame using a program called BikeCAD. The program is a user-friendly way to quickly input frame dimensions in order to spit out the necessary lengths and angles at which to cut tubes. The frame geometry that we decided to use was a cross between that used on the Ted Wojcik Monkeybutt and the Felt Nine that I demoed at Interbike East early this past fall. I decided to build it around a Fox F29 100mm fork, the dimensional specifications for which can be found on the Fox website if you really dig for them.

Once the geometry was decided upon we were able to start to set up the frame jig. The first step for doing so was to set the bottom bracket drop. Toby's frame jig is made such that the bottom of the main member, once the table of a milling machine, is coincident with the centerline of the dropouts. That means that measuring the BB drop is a simple as using a dial caliper to measure the distance from the bottom of that main member to the center of the BB post. There is a mark on the BB post which makes it easy to find the center. The next step in setting up the jig was to adjust the angles of the arms which hold the seat tube, top tube and the head tube. This was done using a digital protractor using the main member as the reference point on which to zero the protractor.

bottom bracket drop. Toby's frame jig is made such that the bottom of the main member, once the table of a milling machine, is coincident with the centerline of the dropouts. That means that measuring the BB drop is a simple as using a dial caliper to measure the distance from the bottom of that main member to the center of the BB post. There is a mark on the BB post which makes it easy to find the center. The next step in setting up the jig was to adjust the angles of the arms which hold the seat tube, top tube and the head tube. This was done using a digital protractor using the main member as the reference point on which to zero the protractor.

The head tube is the first to be cut. It was rough c ut to length using a cutoff saw with an abrasive wheel and then chucked into a lathe and faced to square off the end that was cut. The head tube is then placed into the jig between two conical pieces of aluminum that keep it centered on the rod in the front of the jig. The second tube to cut and placed in the jig in the seat tube. The seat tube is rough cut to the approximate desired length and then metered to the proper length at a 90 degree angle using a hole saw equal to the size of the BB shell. This may seem obvious, but it is far too easy to mistakenly grab the hole saw the diameter of the tube being cut rather than the one which the tube is being mitered to join.

ut to length using a cutoff saw with an abrasive wheel and then chucked into a lathe and faced to square off the end that was cut. The head tube is then placed into the jig between two conical pieces of aluminum that keep it centered on the rod in the front of the jig. The second tube to cut and placed in the jig in the seat tube. The seat tube is rough cut to the approximate desired length and then metered to the proper length at a 90 degree angle using a hole saw equal to the size of the BB shell. This may seem obvious, but it is far too easy to mistakenly grab the hole saw the diameter of the tube being cut rather than the one which the tube is being mitered to join.

Next we cut the top tube. The first miter wa s made in the head tube end to ensure that there would be plenty of material at that end as it will see much more stress than the seat tube due to the long moment arm of the fork acting on it. The seat tube end is then rough cut to the approximated finish length, then mitered to the proper length. After the miter was made, as happened after each miter, the belt sander was used to deburr the outer diameter of each miter, as well as to remove the areas of the tubes that were made excessively thin by mitering them.

s made in the head tube end to ensure that there would be plenty of material at that end as it will see much more stress than the seat tube due to the long moment arm of the fork acting on it. The seat tube end is then rough cut to the approximated finish length, then mitered to the proper length. After the miter was made, as happened after each miter, the belt sander was used to deburr the outer diameter of each miter, as well as to remove the areas of the tubes that were made excessively thin by mitering them.

The miters in the top tube are more difficult to set up than that of the seat tube. The head tube cut was done at a 93.5 degree angle as shown on the frame blueprint above. It was cut using a hole saw equal to the diameter of the head tube. Before the second miter can be made in the top tube we install a piece on the jig to properly orient the tube to ensure that the second miter is cut in the same plane as the first. The piece that we added to the jig is a cylinder the same diameter of the head tube and it swivels freely such that it seats fully in the previously mitered end while allowing the tube to be clamped securely into the mitering fixture. The end with the cylindrical swiveling piece can also slide up and down the fixture to adjust the length of the tube. A scale is on the top of the fixture and allows for quick setup. For this miter the jig was set at 94 degrees, a 30mm hole saw used and the length set to 584.4mm.

Before the second miter can be made in the top tube we install a piece on the jig to properly orient the tube to ensure that the second miter is cut in the same plane as the first. The piece that we added to the jig is a cylinder the same diameter of the head tube and it swivels freely such that it seats fully in the previously mitered end while allowing the tube to be clamped securely into the mitering fixture. The end with the cylindrical swiveling piece can also slide up and down the fixture to adjust the length of the tube. A scale is on the top of the fixture and allows for quick setup. For this miter the jig was set at 94 degrees, a 30mm hole saw used and the length set to 584.4mm.

The down tube is mitered similarly to the top tubes, only with different angles and hole saws. The one added twist to it is that a down tube of this large a diameter not only intersects the BB shell, but also the seat tube. We approached mitering this tube by first mitering the down tube at the head tube end, then the BB end. Lastly, we used a permanent marker to roughly mark the depth of the necessary notch. The mitering jig was then set to the angle of 55.7 degrees and the hole saw plunged to saw up to the marked length.

The main tubes were then placed in the frame jig to check fit. Since the angle was set on the head tube but not the position we used the top tube and down  tube as guides to places the head tube by sliding it until it fit snugly. We then could check to be sure that all of the miters were tight and to the proper lengths. We measured the lengths of the tubes with a tape measure and inspected the miters visually. The miter in the down tube which provides clearance for the seat tube needed to be adjusted. We had to re-miter it twice to get it right, but it fit nicely when we were done.

tube as guides to places the head tube by sliding it until it fit snugly. We then could check to be sure that all of the miters were tight and to the proper lengths. We measured the lengths of the tubes with a tape measure and inspected the miters visually. The miter in the down tube which provides clearance for the seat tube needed to be adjusted. We had to re-miter it twice to get it right, but it fit nicely when we were done.

Once the fit of the main tubes was verified we prepared them for welding. The insides were cleaned using a die grinder with a sanding drum at each end. Then the inside and outsides were washed with non-chlorinated brake cleaner or lacquer thinner.

Toby had me miter a few scrap pieces of tubing to fit practice welding on. They were mitered to fit and cleaned as the main tubes were. By this time it was 7pm and we decided to call it a day.